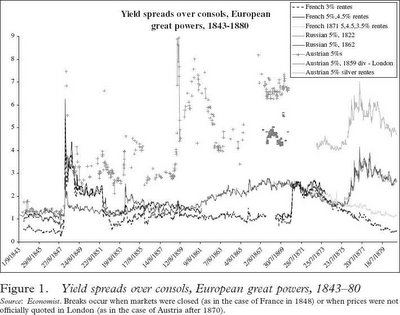

Hablo de la Primera. Me crucé con un paper de Niall Ferguson (posiblemente el historiador joven más celebrado del momento) donde mira los riesgos soberanos de los cuatro Big Powers del continente (Austria, Francia, Prusia/Alemania, Rusia) entre mediados del XIX y 1914. La paradoja es la siguiente: hasta 1880, los eventos políticos/bélicos parecían tener un impacto inmediato y fuerte en los riesgos soberanos: el 48, Crimea, las guerras austríacas contra Cavour y contra Bismarck, la guerra francoprusiana, todo eso se refleja rápidamente en los riesgos. No sé si se entenderá mucho el gráfico:

The main question addressed is why political events appeared to affect the world's biggest financial market, the London bond market, much less between 1881 and 1914 than they had between 1843 and 1880. In particular, I ask why the outbreak of the First World War, an event traditionally seen as having been heralded by a series of international crises, was not apparently anticipated by investors. The article considers how far the declining sensitivity of the bond market to political events was a result of the spread of the gold standard, increased international financial integration, or changes in the fiscal policies of the great powers. I suggest that the increasing national separation of bond markets offers a better explanation. However, even this structural change cannot explain why the London market was so slow to appreciate the risk of war in 1914. To investors, the First World War truly came as a bolt from the blue.

Curiosamente, después de 1880 los rendimientos de los bonos europeos empiezan a acercarse al consol (el benchmark de la época, equivalente a lo que hoy es el bono de USA a 10 años). Mejor dejemos que Niall resuma su argumento, y el que quiera el PDF se lo mando:

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario